[Vue.js] A note on Vite, a very fast dev build tool

Vite is the brand new development and build server proposed by Evan You, which is fast. Very fast. And it is framework-agnostic, so its scope is not reduced to Vue apps.

Indeed, Vite takes advantage of the browser implementation of ES modules (or ‘JS modules’ or ‘EcmaScript Modules) to serve modularized applications instead of using bundles.

Nb: Vite still uses bundles for production (based on Rollup, which itself is based on ES modules)

Vite also supports HMR (Hot Module Reload) for Vue, React, Svelte. So, this combined with ‘unbundled development’ (a term coined by @FredKSchott) enables Vite to instantaneously update a running app with any code changes, and to free the front-end developer from the wait for compilation.

Nb: Vite means ‘fast’ in French [drapeau]

So how does this technological wonder works?

[Note: a consistent part of this article gives an overview of Vite’s concepts and of how Vite works, but is not strictly relevant to use Vite. The user in a hurry can go directly to the parts II and IV, which present Vite’s main features and gives some hints on how to “migrate” to Vite.]

Table of contents:

- I. [Reminders] Core concepts:

- II. Vite’s features:

- III. The logic behind Vite:

- IV. Vite’s magic: instantaneous browser updates

- V. How can I ‘migrate’ my app to use Vite?

I. [Reminders] Core concepts:

A. Bundled vs unbundled development:

You can find here propper definitions by @FredKSchott, which I summarize here:

- ‘bundled development’ is the process we cope with every day: the source code, which is not directly understandable by browsers, is compiled and bundled. The main reason for bundling is that browsers do not understand modules formats used in the source code (cf B.), so we have to concatenate everything into huge scripts. The pain point here is that, for any modification done in the source code, part or all of the application has to be rebuilt, which takes time.

- ‘unbundled development’ is the idea that, since we have now an official module system in JavaScript, everybody can understand each other and we can skip the bundling process. The interesting thing is that, on source code modification, we do not need to rebuild everything, but to compile (if needed) and ship only the modules affected by the modification. And this takes few milliseconds.

B. Why bundled development?

This is a bit next to the subject, but I think it is a legitimate question: why have we been imposing this to front-end developers for years?

The first thing we can note is that, before supporting ES modules (so until late 2017 for Chrome, early 2020 for Edge), browsers did not implement any standard module system. So source code, which was modularized, had to be bundled for browsers.

By implementing a ‘module system’, I mean:

- supporting a module format

- implementing a module loader

Could have the community provided a browser-friendly module system then?

Probably, if there had not been a bigger problem behind: until ES6, there was no official module format in JavaScript. This, fortunately, did not prevent the community to use the module pattern, by creating its own module format. The thing is that not one format was defined, but numerous ones: CommonJS (CJS), Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD, Universal Module Definition (UMD). Plus Global (in the end, the only universal available format). Plus frameworks using their own module systems (Angular JS scope and dependency injection). All these were great workarounds but had the major inconvenience of being more than 1.

for node.js environment, CJS has been imposed from the beginning, so this problem is purely front-end.

Why did not one ‘won’ over others? CJS was not browser-friendly. AMD was browser-friendly and had browser compatible loaders (require.js, curl.js) but dependency management was difficult to configure. I guess UMD came too late.

Therefore, it has been commonly agreed that the best solution was to use a bundler (namely Webpack) which could understand all module formats and compile them into a good old script.

C. Browser ES modules implementation:

Here we are: all major browsers (excepted IE) support ES modules!

A quick reminder on the most important differences between modules and regular script (this is not exhaustive):

- lexical top-level scope (a variable declared in the module scope is not reachable from the global scope, as it would be in the case of a regular script)

thisrefers toundefined(instead of the globalthis)importandexportsyntax

Browsers expose two ways of handling static imports:

- with the

scripttag, by giving the newmodulevalue to thetypeattribute (generally used for entry points):<script type="module" src="./main.js"></script> - with the

importsyntax (the script loaded will be by default treated as a module):import App from “/js/app.js"

Both of them triggers an HTTP request to load the file app.js. In particular, the import syntax lets us easily import nested dependencies, which will be loaded layer by layer.

As soon as there are few layers of dependencies, module imports can lead to a cascade of HTTP requests. Therefore, this not suitable for production (more details on this here (src: Google V8) )

So the browser works like a standard module loader: any new module fetch is added to a dictionary where it is keyed by URL. Then, when the whole dependency graph has been loaded, modules are instantiated (from the most nested to the top), their exports are made available, and only then the most up code will be executed.

a specificity worth mentioning of browsers modules implementation: the module specifier (the module path module) must be an URL, bare imports are not supported.

An important thing to notice though is that any module is imported only once (if it is required twice, the browser recognizes its specifier and gets it from its storage). This point will be useful to understand how Vite updates browser on source code change.

Following ES modules specs, browsers also implement the import() method which enables dynamic imports - this method is asynchronous and returns a promise:

import("/js/app.js)".then((m) => { // use module })

Dynamically imported modules are added to the dictionary containing other modules and instantiated, and then can be used as regular modules. As we will see, Vite relies on this feature for updates.

For more information browser ES module implementation, have a look at this awesome in-depth article from the Mozilla Team on how this works internally.

D. Unbundled development:

With the implementation of ES modules, ES based servers appeared: ES dev server, Snowpack, Vite.

So how Vite differs from SnowPack and es-dev-server (refs here and here)?

- on development, Vite supports HMR (which is also the case for Snowpack, but only since v.2), and has very ‘fine-grained’ HMR support for Vue apps

- on production, Vite uses Rollup, which, being based on ESM, can produce smaller bundles

II. Vite’s features:

This part is much inspired from this tweet from Evan You.

A. Generalities:

Vite is a development server based on ES modules and a production server based on the bundler Rollup (which itself relies on ES modules). Even though Vite has built-in support for Vue apps (this point is being discussed here), Vite is framework-agnostic and can support other frameworks with plugins. It currently has working plugins for React, Preact and Svelte. Also, VitePress, a static site generator based on Vue and Vite (“VuePress’s brother”) is currently under development.

Vite is customizable by adding a vite.config.(j|t)s file to the project. The file (ESM or CJS) has to export an object whose type is defined here. We will see examples in B and C.

B. On development:

As seen in I. A and D, Vite serves source files “directly” via ES modules, without a bundling step. To be able to do this, Vite can compile on the fly several kinds of files into ES modules:

- Vue’s SFC

- resources such as CSS files or assets, which, like with Webpack, can be directly imported in JS code. About CSS, Vite supports CSS pre-processors and PostCSS

- TypeScript and JSX files

Vite handles this via a series of Koa middlewares, which look a bit like Webpack loaders.

Vite is built with the Koa framework

Vite supports HMR (Hot Module Replacement) for all the frameworks mentioned in A. Thanks to this, on source code change, Vite only updates in browser modules which have been changed instead of reloading the page. Combined with unbundled development, this is the key that makes Vite’s magic (cf III.).

Customization:

- to handle custom files transformation, koa middlewares can be added to the config file (cf A)

- for SFC, to add a plugin to handle custom blocks, a transform function (

code => trasformedCode) has to be added to the config file - to add HMR support for other frameworks, an API is available

C. On production:

Vite relies on Rollup, which is based on ESM. It is already configured to ‘mirror the dev server’.

Customization:

- custom Rollup plugins can be added to the config file

D. External dependencies:

This is an important point: Vite only handles dependencies which provide a distribution in ES format (excepted for dev dependencies). If not, Vite will either attempt to ‘statically’ convert it into a ES module, which is likely to trigger an error on runtime (see bellow), either exit with a warning:

// the warning

Tip:

Make sure your "dependencies" only include packages that you

intend to use in the browser. If it's a Node.js package, it

should be in "devDependencies".

This might be the most serious problem for migrating an existing application to Vite because, even if ES distributions should be, at some point, the norm, currently many packages do not provide it (cf I. B and III. A.).

This raises a question: will Vite choose to really support other formats than ESM (as, for example, Snowpack does -ref)? According to this issue, it will not, because it would require to implement a dubious solution.

Indeed, it would require to convert non-ES modules into ES modules, which can be done by, for example, Rollup (with the plugin @rollup/plugin-commonjs). But, since non-ES modules rely on dynamic logic which is difficult to statically analyze, an ESM bundler would transpile them into a single export.

The problem is that we are used to a much better granularity with non-ES modules. For example, in React, even if React distribution is not available in ESM, we can do this: import {x} from 'React'. This is possible thanks to some tricky ‘hack’ (code compilation and runtime helpers to handle the dynamic logic).

see also the example IV. A. with Lodash

So Vite, to handle that, would have to implement this solution, which, in addition to being hacky, is far from Vite’s primary design (work with ESM). So the team has chosen to only ES distributions.

For React, the team recommends to use the ESM React builds

@pika/reactand@pika/react-dom(cf IV. C.)

E. What Vite does not:

For now, what is out of Vite scope (ref):

- linting

- type-checking on development process (but does it on build) (also see here some limitations on TypeScript)

- running tests

- formatting code

The idea is that these tasks can be handled by other tools (IDEs, test libraries…), and setting them in Vite would be redundant.

III. The logic behind Vite:

A. Unbundled development in practice:

As previously mentioned, the idea is to use the native ESM support to load and instantiate the source code and external dependencies, instead of serving bundles.

To better apprehend how satisfying this is, I think the best is to view it. Here the top-level module (the entry point) of a standard Vue app, as served to the browser by Vite:

<script type="module" src="./main.js"></script>

// main.js

import { createApp } from '/@modules/vue'

import App from '/App.vue'

import '/index.css?import'

createApp(App).mount('#app')

And that’s all.

So everything will be, layer by layer, imported from here via a cascade of module imports (HTTP requests). Also, as you can see, this is extremely close to the main.js file in our source code: here only module specifiers have been changed to be browser compatible (cf I. C.); there will be more code transformation later though.

Once the whole dependency graph (cf Part I.) has been imported, the browser instantiates module from the bottom (modules which do not have dependencies) to up (here the upper script). So, in our example, all the dependencies are ready when Vue bootstrap process starts.

B. Nested dependencies management:

A crucial part of Vite’s job is to rewrite modules imports before serving them. Indeed:

- browsers don’t understand bare imports (cf I. C), but we use generally bare imports in source code since they are supported by bundlers. So Vite has to turn all module specifiers into URL

- dependencies of nested dependencies have ‘nested’ URL. Since Vite has a stateless (HTTP) API, it doesn’t know if an import is required from a top or nested dependency. So all module specifiers have to be rewritten to be absolute.

In the case where the dependency is modularized (not ‘bundled’ into one big ES export) this can lead to very numerous HTTP requests, which is not a problem in a development environment.

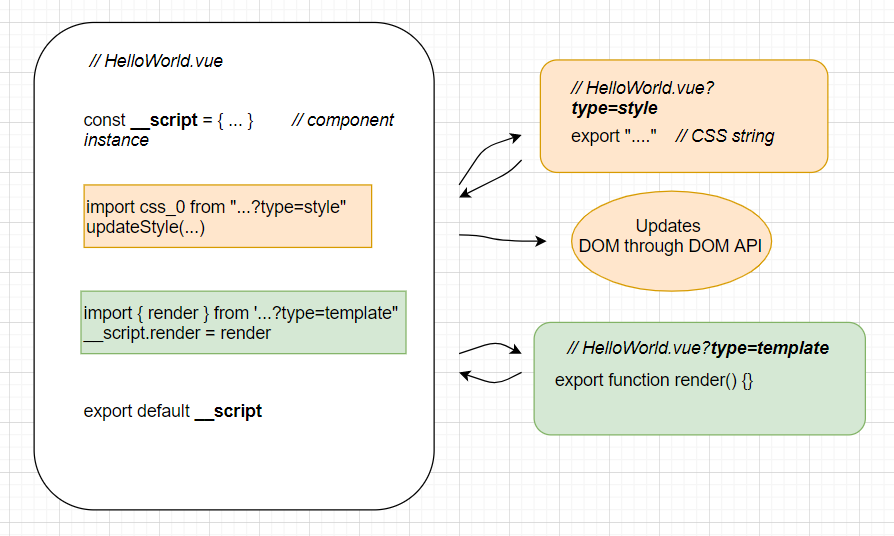

C. Code transformation: example with SFC compilation & transpilation

As we mentioned in II., Vite performs code compilation on demand, with features inspired by Webpack loaders.

Concerning SFC, Vite transforms each SFC bloc into modules (which all are dependencies of the “script” bloc module). For this, it relies heavily on the Vue Compiler, which, in particular, parses .vue files and produces render functions:

- when the server gets a request matching the pattern

/<componentName>.vue, it first extracts thescriptblock, performs the transformations described above, adds imports for ‘style’ and ‘template’ modules and adds callbacks to handle these imports and returns the module (HMR, DOM update) - then the style block is compiled into a CSS string, wrapped into a module and returned

once loaded, it is handled by the module previously imported, and will be given as a parameter to a function updating the DOM

- then the template block is compiled into a render function, wrapped into a module and returned

once loaded, it is appended to the component instance under the

renderproperty

This schema summarizes the steps described above:

IV. Vite’s magic: instantaneous browser updates

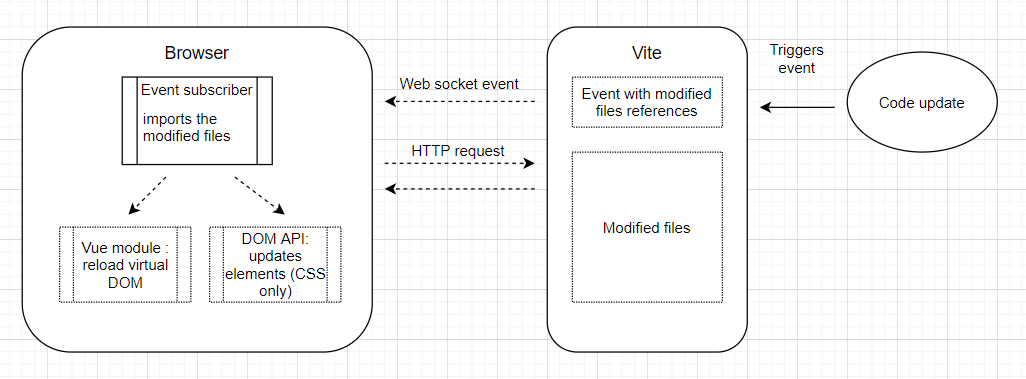

A. Vite re-imports only the modules where a modification has been made:

Vite leverages here ES dynamic modules imports (cf Part I.) and HMR (for Vue, React, Preact, Svelte).

Concretely, Vite, in dev mode, watches files (as most dev servers). When it detects that a file has been modified, it emits a web-socket event to the browser, like this one:

{path: "/components/HelloWorld.vue",

timestamp: 1590935911313,

type: "vue-reload"}

As you can see, this message contains a file path: this is the module specifier of the module to update. Then, the listener of the event imports the updated module and gives it as a parameter to a HMR dependency which will update the virtual DOM (or the DOM in case of CSS):

// hmr

// in case of a type “vue-reload”

case 'vue-reload':

import(`${path}?t=${timestamp}`)

.then((m) => {

__VUE_HMR_RUNTIME__.reload(path, m.default);

console.log(`[vite] ${path} reloaded.`);

})

.catch((err) => warnFailedFetch(err, path));

break;

Here is the source code.

Why is there a timestamp in the URL passed to the

importfunction? Because browsers register modules into a dictionary where they are keyed by URL. So, if we passed only the URL to theimportfunction, the browser would recognize it and it would directly return the module which has been stored during the bootstrapping of the app.

So, in addition to skipping any bundling process, thanks to the granularity offered by the module system, it can reload precisely only the very piece of code updated. Simple and efficient!

B. No dependency is re-imported:

But what happens when the updated component has dependencies and presents import statements? Are they re-imported as well?

Of course not, and here again Vite takes advantage of ES modules: when it returns an updated module, it doesn’t change the URL of its dependencies. Since the browser recognizes the module specifiers of the dependencies, it will fetch these modules in its cache instead of triggering HTTP requests to import them.

And what if a module is modified and one of its dependencies at the same time? These modifications are handled in two different sequences (two distinct events are emitted).

V. How can I ‘migrate’ my app to use Vite?

Nb: There is already a detailled documentation plus tutorials on how to create an app with Vite, so I skipped this point.

Nb2: At the time of writting, there is no documentation, official guideline neither tutorial on how to migrate an existing app to Vite. So, since the following part is completely experimental, any comment or feedback would be most welcome.

A. For any app:

Even though Vite is primarily designed to work with Vue, it is framework-agnostic, and can be ‘customized’ to other frameworks through plugins. For example, it has already a workable plugin for React (cf IV. C.). But, plugins apart, there are some operations to perform which are common to any migration, and which are described bellow.

- Obviously, one thing to do is to add Vite :D :

yarn add --dev vite - [this might be the biggest pain point in the migration process] Change all dependencies distributions to ES modules. Indeed nowadays, most NPM packages are exported in CJS and/or in AMD, and unfortunately, not all of them provide ES builds. But Vite, for now, only supports ES modules, and will not find, for example, a dependency with a CJS distribution (cf II. C.).

Example: Lodash

Let’s say we have imported Lodash in our project:

"dependencies": {

"lodash": "^4.17.19"

},

And we use it in our code:

import {cloneDeep} from 'lodash'

const a = {toto: 3}

const b = cloneDeep(a);

Then, when we run this code, the browser will throw this error:

Uncaught SyntaxError: The requested module '/@modules/lodash.js' does not provide an export named 'cloneDeep'

Why does this happen? Because Lodash standard distribution format is CSJ, so Vite will try to convert it in an ES module (thanks to Rollup), but, because of the dynamic logic of CJS, Rollup cannot statically analyse it. So it will convert the whole lodash library in one module, and ship it to the browser. But, since the browser is execting one precise module (and not the full library), it throws an error. We are exactly in the case described in II. D.

But how come this usually works? Well, this is possible thanks to a Webpack ‘hack’, that Vite doesn’t wish to implement (see II. D.)

Fortunately, Lodash provides ES build.

Actually Lodash provides the possibility of generating an ES build through the CLI, which actually adds a bit of complexity. This shows that, even for a widely used library as Lodash, using ES builds is not as convenient as other distributions.

Anyways, hopefully ES distributions shall become one day the norm standard, so this problem would resolve by itself at some point.

B. Vue app:

In the case of a Vue app, here are the steps to do (in addition to the steps exposed in A.):

- Since Vite is only compatible with Vue 3, first thing is (if needed) to upgrade to Vue 3. For this, you can run the following Vue CLI plugin:

vue add vue-next - [optional] you can remove CLI packages. But, if you are using some CLI feature with are not supllied by Vite (see running tests below), you may want to keep this package:

yarn remove @vue/cli-service - change the `scripts` in `package.json`:

"scripts": { - "serve": "vue-cli-service serve", - "build": "vue-cli-service build", + "dev": "vite", + "build": "vite build" }, - (this is conditioned with your entry point `index.html` - here we use the default entry point generated by the Vue create-app) add the import of the top-level module in the entry point:, remove all that is related with Webpack:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1.0"> - <link rel="icon" href="<%= BASE_URL %>favicon.ico"> - <title><%= htmlWebpackPlugin.options.title %></title> + <link rel="icon" href="/favicon.ico"> + <title>My new Vite app!</title> </head> <body> <noscript> <strong>We're sorry but ....</strong> </noscript> <div id="app"></div> - <!-- built files will be auto injected --> + <script type="module" src="/src/main.js"></script> </body> </html>

I guess there will at some point a Vite plugin to handle these little hacks (from step 4).

Running tests:

Vue CLI has plugins dedicated to running unit and end-to-end tests (@vue/cli-plugin-unit-jest, @vue/cli-plugin-e2e-nightwatch…), whereas Vite doesn’t offer yet any ‘test’ plugin (cf II.D). So one option would consist in keeping the CLI package to run tests. But, AFAIK, currently these plugins do not work well with Vue 3. So, for now, you may have to remove the plugins, and to manually configure test dependencies (Jest, etc) and run them via the dependencies binaries. This will probably change in the coming weeks, so this article will be kept updated with this.

C. React app:

- [important] Since React is distributed in UMD, and not in ESM (cf I.B), we have to use an ESM build.

@pika/react and @pika/react-dom are packages built by @FredKSchott (SnowPack) automatically parse React builds to output them in ES modules. The repo checks daily for React updates, so it is always up-to-date.

"dependencies": { - "react-dom": "^16.13.1", - "react-dom": "^16.13.1", + "@pika/react": "^16.13.1", + "@pika/react-dom": "^16.13.1" }, - [this might be an issue] You may unfortunately have to remove non-dev dependencies which rely on React (non ESM distribution):

Otherwise, Vite will shut down the process with this message:

"dependencies": { - "@testing-library/react": "^9.3.2" },This is discussed in II. D. and in IV. A. For testingMake sure your "dependencies" only include packages that you intend to use in the browser. If it's a Node.js package, it should be in "devDependencies". - Add, at the root level, a Vite config file informing that Vite needs to use the React plugin (details here)

- Change the extension of files containing JSX from `(j|t).s` to `(j|t).sx`

- (this is conditioned with your entry point `index.html` - here we use the default entry point generated by the React create-app) add the import of the top-level module in the entry point:

<body> <noscript>You need to enable JavaScript to run this app.</noscript> <div id="root"></div> <script type="module" src="/src/index.jsx"></script> </body>

Running tests: Since React testing utilities depend on React non-ESM distribution, you may have to use directly testing libraries (without React utilities). Or to wait for React to provide an ESM distribution, which should happen in v. 17 (2020).

Summary:

Vite is a development and production server based on ES modules.

In development, Vite relies on native ESM instead of bundles and compiles on the fly required files into ES module. This, combined with HMR support for Vue, React / Preact, Svelte, Vite can update, on source code change, a running application in browser instantaneously.

In production, Vite also offers a bundled build based on Rollup, which guarantees highly optimised bundles (thanks to ESM support).

For now, Vite is still experimental, hence we are looking forward to future developments, and, perhaps, an integration in Vue or other frameworks standard configuration. But there is no doubt on one thing: this will definitely improve front-end experience.